Classics in the History of Psychology

An internet resource developed by

Christopher D. Green

ISSN 1492-3173

(Return to Classics index)

Studying the Mind of Animals

by John B. Watson (1907)

Instructor in

Experimental Psychology, University of

First published in The World Today, 12, 421-426.

Posted August 2004

The average person is interested in animals and particularly in what is getting to be called animal psychology. It is one thing, however, to watch the habits of birds and foxes, and quite another to experiment with animals as psychologists experiment in their laboratories. Dr. Watson is one of the most successful of the younger workers in this new and fascinating field. The importance of the conclusions which he states in his brief paper will be apparent to any one who has ever speculated on the intelligence shown by his favorite dog or cat, or who has ever watched trained animals. His paper is further important as an illustration of the difference between genuinely scientific observation and the writing of story books. Dr. Watson is now in the midst of other experiments which are likely to prove not only of interest but of real importance to the psychologist and nerve specialist.

Is it a wild speculation to suppose that we shall ever be able to state just What goes on in the mind of our dog as he bays at the figure of the man in the moon, or growls at the shadow of some cat which lives in the neighboring yard? Can we ever be sure of what is passing in his mind as he now yelps with delight at the sound of our voice, then leaves as to "smell and make up" with some wandering and friendless cur? The problem is not so difficult as it appears at first sight. Insuperable difficulties confront us if we attempt to get into the mind of the animal and directly see what is going on there. Yet hardly other than those that confront us when we try to figure out the mental state of the man who, after running for six blocks, fails to catch the rear platform of the down-town express. In the ease of the man, however, we feel reasonably sure that we know what he is thinking. True, we can not get into his mind and see for ourselves just what ideas are rising, waxing and waning and rising again we may be too far away to question him or to hear what he is saying; how then do we come by this proximate knowledge of what he is thinking? By noting carefully what he does!

If we think carefully of the may find out what our human companions are thinking, we can not fail to be struck by the fact that our only method for obtaining such information is to be had by observing their conduct. If they act in the way we should act if we were placed in similar circumstances, we unhesitatingly [p. 422] assume that their mental processes are similar to our own. This same method ought to hold good in the study of animals, provided we carry out the method with the same care in the animal world that we employ in the study of men. If it is objected that language, the ability to communicate thought, forever makes the study of man different from that of the animal, we must at once take the position that language after all is nothing but a highly elaborated and complex form of behavior. We should further maintain that if the behavior of any animal were as varied and intricate as that of man, such an animal would necessarily exhibit language in some form or other which would be entirely comparable in complexity with the language of man.

The possibility of learning more about the mental life of animals becomes a probability when we consider that our knowledge of the mental processes of infants, children and defective individuals is obtained almost entirely without the aid of language. The moment we take this broader point of view, that the behavior of man expresses his psychology, and are willing to admit that we can scientifically study his behavior, it follows at once that we can build up an animal psychology, because we can study the behavior of animals just as scientifically as we can study the behavior of man.

The study of behavior thus becomes a broad science; normal adult human psychology forms only a part of its subject matter. The psychology of infants, of children, of the feeble-minded, of primitive peoples, of animals, all form a part of the world to be observed by the psychologist. The behavior of animals alone is a much broader field than is usually supposed at first glance. Mammals, birds, fishes, even the lowly unicellular organisms, and possibly the sensitive plants, are all embraced in any complete scheme of the study of mind.

With such a vast system of work before him then, the animal psychologist will not be downcast if after years of patient study he fails to find his animal reasoning, imitating, imagining. By his toil he will have established a series of facts, and this will mean far more to him and to his science than that he should gratify his anthropomorphic emotions, as do many so-called naturalists, at the expense of the accuracy of observation.

So impressed have psychologists become of the truth of these facts that we find latterly in many of the larger universities especial facilities provided for the study of animals. Men trained both in biology and in psychology are set aside to untangle the skein of the mental life of these animals. In a few years we can safely predict that one of our familiar adages can be made to read, "What is a psychology laboratory without a menagerie" and the moiety of truth expressed in the new version will not be less than is found in the old. Furthermore, the time is not far distant when experiment stations will be established for the exclusive study of the minds of animals.

Surely the evolution of mind is no less worthy of study than is the evolution of the bodily structure! Considering the enormous number of exact studies on the structure of animals we have already at our command, we firmly believe that from now on, the evolutionary study of behavior will yield far more fruitful results for the guidance of human conduct than will further studies on morphology alone. And in saying this, we do not mean to decry the usefulness of such structural studies in the past nor their possible value in the future.

Let us turn to consider a, little more intimately the way our well-trained student of animal psychology pursues his work. In the first place, he must be prepared to watch his animals day in and day out, not for weeks, but for months. He must spend the greatest care upon them, doing his best to keep them in uniformly good condition. Time and money are spent upon their diet and the utmost precautions are taken to provide them with a warm and cleanly habitation. The higher we ascend in the animal scale, the greater care we must exert to keep our animals happy, and finally, when we reach the higher mammals, the conditions maintained for their care are not unlike those obtaining in any (well-kept) nursery.

The necessity for such care will be appreciated when we consider the fact that the uniformity of the behavior of the animal depends upon his bodily condition. If an animal is stuffed one day and [p. 423] starved the next, his behavior will show it; if he is freezing at one time and suffering with heat at another, his reactions will alter accordingly.

The next most important concern of the investigator is to obtain the tamest animals which can be purchased or bred. This likewise calls for a vast expenditure of time on his part. To beep any animal gentle, it is necessary to handle him every day. Unfortunately, this precaution has not been sufficiently observed even by trained investigators. The reason for this state of affairs is not far to seek. The conditions at the universities where animal psychology is studied are not ideal either for the animal or the student. Not enough space can be obtained and the men who are actually engaged in the work can devote only a small part of their time daily to it. With the coming of better conditions in our laboratories this now more or less neglected factor will receive attention.

The animals which are later to be observed should be taken in hand when they are young. Only in this way can the student of their behavior learn to know the "personal side" of his animal. This need allows itself still more clearly when we consider the numberless chance associations which animals either establish for themselves or with the aid of their attendants. Animals which have once lived in public gardens are quite useless to serve as subjects for scientific studies on behavior.. The otherwise careful English investigator, Hobhouse, did not fully recognize this fact, and some of his conclusions as regards the presence of the higher mental processes in animals can not be accepted until the work is done over again upon animals whose prior history is known.

To make this matter clearer, suppose we take a

specific example, one chosen front the writer's experience with Rhesus monkeys.

It would be a very simple matter for a fourteen months' old child to learn to

pull in, by means of a very light toy wooden rake, an object which it could not

reach with its hands, and yet, Jimmie, a very tame Rhesus monkey of mine, spent

many days in trying to learn this simple act and had not learned to manipulate

the rake when our patience ran out. Jimmie was kept moderately hungry at the

time of the experiments; he was tethered just out of reach of some very

tempting food (

Now what happens when the grape has been eaten? The rake is still within his reach and the grapes are still outside the pale! Does he perceive the relationship existing between "food out of reach, rake will lengthen paw, ergo, use rake?" Not Jimmie! And he is the brightest of six! As long as you mill kindly hook the blade of the rake around the grape and extend the handle toward him, he will condescend to pull in the rake and consequently the grape, but he has never yet both pushed out and then pulled in the rake of his own initiative. If Jimmie had been purchased from a zoölogical garden and had previously learned such a trick or a similar one, and had we tested him, ignorant of his accomplishment, we might have a far different opinion of his mental make-up from the one we now have. Certainly, no one who has followed the behavior of Jimmie and his five mates for one year would be inclined to accede to Mr. Garner's wonderful statements concerning the presence in monkeys of the "powers" of reasoning imitation, etc.

However, even the legitimate psychologists have not lost hope, as yet, of finding these mental functions in animals. More and more systematic work is being done along this field and the effort is constantly being made to make our tasks more and more like those to which the animal is accustomed on his native heath. It is perfectly natural for all animals to be hungry and to seek for food even when the obtaining of it offers difficulties.

The desire for food is one source of our control over the actions of our animals. Various forms of "problem boxes" containing food, but which require the moving [p. 424] of some simple mechanism before the food can be obtained, represent one kind of task which the animal is forced to perform. A modification of this method, useful with animals which desire each other's company or the freedom from enclosures, is obtained by placing the animal in a narrow enclosure and putting the food or other animals outside. A twofold stimulus is thus presented -- food and the freedom from restraint. Such a method can be worked very well on a number of animals, cats especially. Problem-boxes can be made very complex or very simple and they can be adapted individually to the sensory and motor equipment of the particular animal under observation. Every animal requires a set of problem-boxes particularly adapted to his anatomical structure and instincts.

Hunger is not the only stimulus which can be used to make the animal form these associations. We said above that the desire (using "desire" in a non-technical sense) for companionship can serve the same purpose as that of hunger. Freedom from a confining space, punishment, words of encouragement and the desire for sexual gratification are other stimuli which can be used with varying success, depending upon the animal employed. The sexual instinct is exceedingly well marked in the monkey and in the rabbit; the cat becomes frantic when confined, the chick is "despondent" if separated from its mates. Students of animal psychology are not all agreed as to the best incentive to make the animal work. Food, however, is the one which has been most widely used up to the present time.

Let us complete the picture of the methods used by our student of animal psychology. His animal is hungry; food is near by, in plain view, or at least within smelling distance, but out of the immediate control of the animal. But the animal must do something, turn a latch, pull out a bolt or gnaw a string before he can obtain the food. Our student sits patiently by with pencil, paper and stopwatch in hand. Each tentative trial, every random and foolish movement of the animal is carefully put down in the notebook. The moment the animal reaches the food, the watch is stopped and a record of the time consumed by the animal in this first "trial and success" is made.

Be the time of the first "success" long or short, accomplished with few random and wild movements or with many, the animal is set to work a second and third time upon the same problem. Only three or four trials can be given to the animal each day on account of the possible dulling of the edge of his appetite, and since only the simplest problems can be mastered in so few trials, the animal is put back into his cage until the corresponding time on the following day. This routine is repeated day by day until the animal can solve the problem without making random movements.

Suppose now we have varied in a number of ways the problems which are presented to our animals, and that we have records of the time and the errors of many animals in solving these same problems, what are we forced to think about the nature of their minds? Surely, if any of our animals could immediately perceive the "hitch" in the mechanism of the box and act upon this perception as an intelligent child would do, the facts would come out in some of the experiments. If one animal could imitate what another animal does, or if he could imitate the actions of his trainer, we should likewise not long remain ignorant of this function in him.

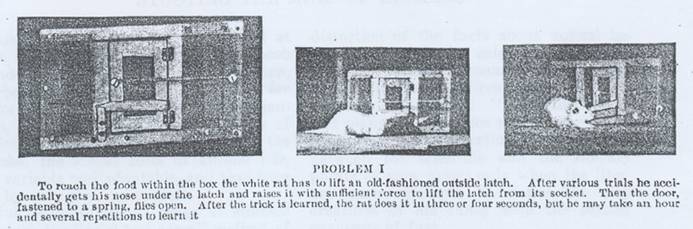

Most of the evidence so far collected, however, points to the fact that if animals possess what in man are called the higher mental functions they keep them pretty well hidden. The majority of animal psychologists now hold that the so-called "trial and error" method of learning is the one typified by the behavior of animals. This method of learning by "happy accident" or chance success, as it is sometimes called, can be illustrated by considering the way the white rat gets into the problem boxes shown in the accompanying photographs. In one of these boxes, the rat has to lift an old-fashioned outside latch. After the trick is learned, he does it in three or four seconds. One seeing only the complete act is wont to express admiration for the rat's cleverness in no uncertain terms. How different would one's view be if forced to watch the whole process of learning!

When the box is first presented to

him, he runs over it and around it, biting at [p. 425] the wires, poking his

snoot or paws between the meshes; leaving this he scampers around and over the

box again; then he sits idly by for a time and makes his "toilet,"

washing his face and hands and fur. This done, he

bounds for the box again. By testing every corner of the box, he

inevitably finds the door and the spring which is attached to it. These will

move when pushed or pulled while the rest of the box is stationary. After

a time, he happens to stick his nose down on the bottom edge of the door,

possibly to investigate a new smell or to bite his toe. He raises his

head suddenly -- and by reason of the physically inevitable fact that by

raising his snout he strikes the underneath edge of the latch with sufficient

force to raise it from its socket, the door will fly open. The problem is thus

solved! This may take anywhere from two minutes to one hour, depending

upon how soon the rat bites his toe underneath

the latch or how soon any

number of other equally happy accidents may lead in the same! way to the same result.

But the second time? Does the rat go to the latch and raise it without useless movements? By no means! In individual cases even, a first success may profit the animal nothing. If a large number of time records, however, are averaged, the time of the second opening of the box is found to be shorter than that of the first; the third shorter than that of the second, etc., until the final time comes to represent that actually required to open the box in the most direct way.

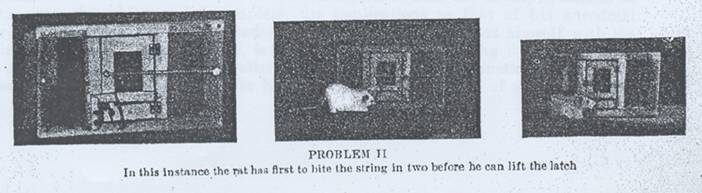

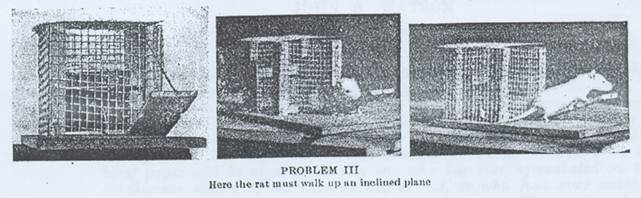

The rat learns to open the

other problem boxes shown in the photographs in this same hit-and-miss

fashion. In Box II, he has first; to bite the string in two before he can

knock up the latch (he never unties the string)! In Box III, the animal

must walk up an inclined plane until the increasing tension on the string

causes the latch holding the door in place to rise from its socket.

These illustrations of the "trial and error" method of learning are chosen from animals which belong to the same genera as man. How do animals lying lower in the scale of development learn? Do they learn at all? These questions at present are somewhat disputed. Loeb holds that all animals which are less developed than the tree-frog show no signs of learning at all. Their movements, according to him, are determined in a purely mechanical fashion. The animals are forced to go hither and thither according to the way light, air vibrations, chemicals or other forms of physical motion brine about changes in the state of tension of the tissues of their bodies; i.e., whether these physical agents directly contract or expand the muscles of the body on the side upon which the stimulus [p. 426] is exerting its force. It may be said at once, that, in this country at least, Loeb stands practically alone in this position. Herbert S. Jennings, who has worked for years upon the behavior of lower organisms, has shown beyond the possibility of a doubt that the reactions of even the amba, the lowest form of animal life, are variable and adaptable, and that they are by no means mechanical.

But determining the range of

animals in which the "trial and error" method of learning can be used

is not the sole, nor in the opinion of this writer at least, the chief problem

of the animal psychologist. A knowledge of the sensory equipment of the animal -- the accuracy, kinds and delicacy of

his sensations -- is indispensable to further progress in this field.

Which of my :animal's senses are his important ones? Are all his senses equally well developed? Do they give him the same information about the outside world as our own give us? Does he see all the colors, for example, as we see them, or does he react only to their brightness? Does he by any chance use senses which man either does not possess at all or else possesses in vestigial form? These questions can all be answered and along with thousands of others must be answered before the fullest knowledge of the origin and the development of the human mind can come.

With even this short and incomplete sketch of what the experimental student of animal mind has to be and to do, is it any wonder that the "literary naturalist" has had to face scathing criticism for his distortion of the facts about animal behavior? Let it be said, however, that there is abundant room for the purely literary treatment of real or fancied incidents in animal life. "Rikki-tikki-tavi" and many other stories might be cited in support of this assertion. The conflict between the scientific and tile literary points of view arises only when the literary man attempts to clothe the airy creatures of his fancy with the somber garments of fact.

In equally striking contrast to our present methods of the study of mind in animals, stand those of the older school of animal psychologists. Read the prefaces to the many books of Romanes, Darwin, Lindsay, Lubbock and others, and see how their "facts" were obtained. Myriads of anecdotes are told of dogs and cats opening latches, of dogs buying penny buns and accepting only the correct change in return for a larger coin, of monkeys making up their own beds. The list is innumerable. These anecdotes were collected by letters, from all parts of the world, taken on trust. But nowhere do you find a complete or even an incomplete statement of the precise way these tricks were learned.

If the material contributed by the present-day student of animal behavior is not so thrillingly interesting as that of the Thompson-Setons, nor so supra-human in its implications as that of his anecdotal friends, he must comfort himself with the thought that in offering it unadorned as he does, he is adding another stone to the ever-growing structure of modern science.