An internet resource developed by

Christopher D. Green

York University, Toronto, Ontario

ISSN 1492-3173

(Return to Classics index)

Oracle [Lat. oraculum, from orare, to speak]: Ger. Orakel; Fr. oracle; Ital. oracolo. (1) The response of a heathen deity to a solemn petition for information or guidance in some matter of importance, ordinarily communicated through a human medium.

(2) In the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures it is used in the plural,

and applied (1) to the special communications of God to or through his

prophets, (2) to the whole body of inspired writings. (A.T.O.)

Order (in biology) [Lat. ordo, order]: Ger. Ordnung; Fr. ordre; Ital. ordine. In biological classification, a group of greater value than a family.

An order usually, but not necessarily, comprises several families. The

use of the term is entirely conventional. See CLASSIFICATION. (C.S.M.)

Order (moral): Ger. (1), (2) sittliche Ordnung, (3) Weltordnung; Fr. ordre moral; Ital. ordine morale. (1) The system of facts and relationships to which ethical predicates are applicable; called also variously the 'world of values,' the 'universe of worths,' the sphere of appreciation of ideals'; in contrast with 'world of facts,' 'universe of science,' 'sphere of description of the real.' See WORTH.

(2) The establishment and maintenance of order in ethical relationships, as opposed to moral disorder; generally in reference to social rights and duties; also with reference to the divine GOVERNMENT (q.v.) of the world. Cf. THEODICY. (J.M.B.)

(3) The order of the universe conceived as making for moral ends.

The relation of the moral to the natural order of the universe is a question which belongs rather to the metaphysics of ethics or moral philosophy, than to ethics proper, or moral science. The Stoics, following Heraclitus, identified the moral with the universal order, finding in both the expression of the common reason. The early British rationalists may be said to take fundamentally the same view, giving it, however, a theistic and less ethical construction. Kant held that the moral order is the order of the noumenal or intelligible world, which transcends the empirical or phenomenal order, and implies a moral orderer, who shall ultimately equate virtue and happiness. For Hegel the moral order is part of the cosmical order, and finds its perfect expression only in the world-state. The evolutionists either resolve the ethical into the cosmical order or make the ethical a more adequate or higher statement of the same world process which produces and includes the cosmic. Huxley, in his Romanes Lecture on Evolution and Ethics, insists upon the antithesis of the ethical to the cosmic process, yet accounts for the former as arising from the latter.

Literature: (3) GREEN, Prolegomena to Ethics, Bk. I; ALEXANDER,

Moral Order and Progress; FRASER, Philos. of Theism; A. SETH, Man's Place

in the Cosmos; HUXLEY, as cited; discussion by ROYCE, BALDWIN, WHITE, in

Int. J. of Ethics (1895); general works on ethics. (J.S.-

J.M.B.)

Ordinance [Lat. ordinare, to order

or arrange]: Ger. Verordnung,

Vorschrift; Fr. ordonnance;

Ital. ordinanza. In religion, a religious rite or ceremony instituted

by divine authority or by the enactment of some ecclesiastical body. (A.T.O.)

Organ [Gr. orgonon]:

Ger. Organ; Fr. organe; Ital. organo. A differentiated

part of an ORGANISM (q.v.) partially independent anatomically and physiologically,

and performing some special active function or group of functions. (C.S.M.)

Organic [Gr. organikoV, pertaining to organs]: Ger. organisch; Fr. organique; Ital. organico. (1) Relating to that which has life, whether animal or vegetable; opposed to inanimate or inorganic. See ORGANISM (vital). But since the peculiarity of living beings is a certain relation of the parts to one another, such that they mutually act and react upon one another so as to maintain the whole in existence, it means (2) that which possesses a similar necessary relationship of whole and part; that which is systematized; that which is an internal or intrinsic means to an end, as distinct from an external or accidental one. This sense shades into teleological and is opposed to MECHANICAL (q.v.).

Historically, the identification of organic with the living comes last. Aristotle uses the term as equivalent to instrumental; even as synonymous with mechanical, i.e. the means that brings about a result. An organic body is one, whether living or not, in which heterogeneous elements make up a composite whole. This sense persists till Leibnitz, who uses the term in a sense easily confused with the modern significance of living, but yet not the same. According to him, that is organic all of whose parts are in turn machines, i.e. implements adapted to ends. 'Thus the organic body of a living being is a kind of divine machine or natural automaton, because a machine which is made by man's art is not a machine in all its parts; for example, the tooth of a brass wheel has parts or fragments . . . .which have nothing in themselves to show the use to which the wheel was destined . . . .But nature's machines are machines even in their smallest part ad infinitum' (Monadology, § 64; see also the Princ. de la Nature, 31).

From this time on, the two elements in the conception (that of composition of parts and of relation of means to end) are intimately connected, and Kant welds them together in his famous definition of the organic as that in which all the parts are reciprocally means and ends to one another and to the whole (Werke, iv. 493). It is this conception of the whole as primary which marks off the conception from the Leibnitzian, in which the distinction goes on ad infinitum. This tends to change the indefinite pluralism of Leibnitz into a systematic monism when the conception 'organic' is applied to the world at large. Cf. LIFE, ORGANISM, and SOCIAL ORGANISM.

Literature: EUCKEN, Philos. Terminol., 26, 138, 153, 202; MACKENZIE,

Introd. to Social Philos. (J.D.)

Organic (in psychology). Characterizing psychological states or functions which are wholly or largely conditioned by physiological processes.

The distinction is usually between 'organic,' 'lower,' 'coarser,' &c., and 'reflective,' 'voluntary,' 'higher,' 'finer,' &c., as in the phrases organic SYMPATHY (q.v.), organic ('instinctive' or 'spontaneous') emotion (cf. BASHFULNESS, JEALOUSY, FEAR), to which are opposed the 'reflective' or, in earlier literature, 'rational' forms of the emotions, &c. 'Sensuous' and 'ideal' are terms sometimes used to cover the same distinction -- which, however named, is open to much ambiguity. In most of the discussions -- notably of emotion -- in which the distinction is made, organic means unreflective, or, as not involving reflection, spontaneous, which last is the most appropriate word. Cf. also REFLECTIVE AND UNREFLECTIVE.

Literature: many of the discussions of REFLECTION (q.v.), passim;

many of the works on EMOTION (q.v.). Special discussions with reference

to 'organic' emotion are: SCHNEIDER, Mensch. Wille; BALDWIN, Ment. Devel.

(chaps. on 'Emotion' and 'Sentiment' in both vols.). (J.M.B.,

G.F.S.)

Organic Imitation: see IMITATION,

MIMETISM, and CIRCULAR REACTION.

Organic Memory: Ger. organisches Gedächtniss; Fr. mémoire organique; Ital. memoria organica. A term suggested by Hering for the functional reappearance of conditions once impressed upon the nervous system, after analogy with conscious memory. (J.M.B.)

Literature: HERING, Memory as a Function of Organized Matter

(Eng. trans.); BUCCOLA, Mem. organica, Riv. di Filos. Scient. (1881); MORSELLI,

Semej. malat. ment., ii. (1895). (J.M.B.- E.M.)

Organic (or Indirect) Selection: Ger. organische or indirekte Selektion; Fr. sélection organique or indirecte; Ital. selezione organica or indiretta. The theory that individual modifications or accommodations may supplement, protect, or screen organic characters and keep them alive until useful congenital variations arise and survive by natural selection. Cf. COINCIDENT VARIATION, and MODIFICATION. The theory of evolution which makes general use of organic selection is called ORTHOPLASY (q.v.).

The theory, it is evident, involves two factors: (1) the survival of characters which are in any way associated by acquired modifications, &c., during periods in which, without such assistance, they would be eliminated -- until (2) the appearance and selection of congenital variations which can get along without such assistance. The second factor is simply direct natural selection; and it is the first which is the characteristic feature of this theory. By the co-operation of the acquired characters a species or race is held up against competition and destruction while variations are being accumulated which finally render the character or function complete enough to stand alone. Illustrations of this 'concurrence' -- as it may be called -- between acquired and congenital characters will be found in the literature cited below. The definitions which follow show differences of emphasis.

In the words of Osborn: 'Individual or acquired modifications in new circumstances are an important feature of the adult structure of every animal. Some congenital variations may coincide with such modifications, others may not. The gradual selection of those which coincide (coincident variations) may constitute an apparent inheritance of acquired modifications;' and of Lloyd Morgan (Habit and Instinct, 315): 'Though there is no transmission of modifications due to individual plasticity, yet these modifications afford the conditions under which variations of like nature are afforded an opportunity of occurring and of making themselves felt in race progress.' It is described by Headley as 'natural selection using Lamarckian methods' (as cited below, 120). Groos, in expounding organic selection, speaks of the effects of imitation as 'keeping a species afloat until natural selection can substitute the lifeboat heredity for the life-preserver tradition' (work cited below, 283).

The relation of organic to natural selection is also involved in the question of the nature and origin of the PLASTICITY (q.v.) which organic selection requires. The different views are (1) that this plasticity is itself entirely due to natural selection (Poulton); (2) that it is an original property of organic matter (Osborn); (3) that there are two forms of plasticity, as indicated under that topic (Morgan, Baldwin), that of which organic selection makes use, however, being largely the product of natural selection.

This general way of looking at certain cases of survival in the struggle for existence was independently arrived at by Ll. Morgan, H.F. Osborn, and J. Mark Baldwin, and the term 'organic selection' was proposed by the last named on two grounds: (1) because the organism, by effecting accommodations, screens its characters, and so gives them a chance of being kept alive; and (2) because the organism thus, so to speak, selects itself; that is, it is its own accommodations which are instrumental in securing its survival. It is the behaviour of the organism, therefore, which is important, and not variations alone, as in simple natural selection generally -- and hence the adjective 'organic.' It is in so far the organic functions -- reactions, struggles, efforts, conscious choices, &c. -- which really count and determine what sort of characters shall be saved by natural selection.

The term 'indirect selection,' which some prefer (Poulton, Morgan), has reference to the way in which natural selection comes into operation in these cases, i.e. indirectly through the saving presence of modifications, and not directly upon useful variations. This term was suggested by an anonymous writer in the Zoological Record. Poulton also used the term indirect in its adjective form in the following (see reference below): 'These authorities justly claim that the power of the individual to play a certain part in the struggle for life may constantly give a definite trend and direction to evolution; and although the results of purely individual response to external forces are not hereditary, yet indirectly they may result in the permanent addition of corresponding powers to the species. The principles involved seem to constitute a substantial gain in the attempt to understand the motive forces by which the great process of organic evolution has been brought about.'

The effectiveness of the method of screening and so accumulating certain variations in producing well-marked types is seen in ARTIFICIAL SELECTION (q.v.) where certain creatures are set apart for breeding. But any influence, such as the individual's own accommodation to his environment, which is important enough to keep him and his like alive, while others go under in the struggle for existence, may be considered with reason a real cause in producing just such effects. Thus by the processes of accommodation, a weapon analogous to artificial selection is put into the hands of the organism itself, and the species profits by it. Headley characterizes this aspect of the case as follows: 'The creatures pilot themselves. . . . Selection ceases to be purely natural: it is in part artificial' (as cited below, 128; see also Baldwin, Amer. Natural., as cited below). Cf. the view of J. Ward called SUBJECTIVE SELECTION (q.v.).

This point of view has had especial application and development in connection with DETERMINATE EVOLUTION (q.v.), which, when organic selection is operative through a series of generations, becomes what is called ORTHOPLASY (q.v.); with the rise of INSTINCT (q.v.); with the origin of structures lacking in apparent utility when full-formed or when only partly formed (cf. EVOLUTION); with correlated variations, co-ordinated muscular groups, &c.) see CORRELATION, in biology, and INTRASELECTION); with MENTAL EVOLUTION (q.v.), and SOCIAL EVOLUTION (q.v.).

That this form of selection is a real factor in evolution, either as taken with natural selection or as a form of original 'self-development,' replacing natural selection (Osborn, citation below), is now widely admitted: among biologists, by Osborn, Wallace, Poulton, Thomson, Whitman, Defrance, Davenport, Conn, Headley, and others; among psychologists, by Morgan, James, Stout, Ward, Groos, Baldwin, and others. It is held, by many of those who accept it, to answer certain forcible objections to the universal application of natural selection in its 'direct' form, and so to render the resort to the hypothesis of the 'inheritance of acquired characters' -- in the absence of positive evidence for it -- unnecessary (cf. HEREDITY). It would seem to be a legitimate resource in the following more special cases.

(1) In cases in which these is possible correlation or association between the organ or function whose origin is in question, and another which is of acknowledged utility: the latter serves as screen to the undeveloped stages of the former.

(2) In cases of CONVERGENCE (q.v.) of lines of descent: certain accommodations, common to the two lines which converge, compel the indirect selection of variations which not only coincide with the individual modifications, but also coincide more and more closely with each other; so in many cases of resemblance due to similarity of function (cf. MIMICRY, 1) and of resemblance in habit and attitude (cf. MIMICRY, 4).

(3) In cases of divergent or POLYTYPIC EVOLUTION (q.v.): two or more lines of variation, being equally available as supports to an essential accommodation or as co-operating factors in it, are therefore both preserved, although they carry, when developed, each its own structural form. There are many cases in the animal world of ANALOGOUS ORGANS (q.v.) which are yet not HOMOLOGOUS (q.v.) -- organs of divergent origin but of common function, and possibly of common appearance -- the rudiments of which may have owed their common and indirect selection to a single more general utility.

Or, again, two or more different accommodations may subserve the same utility, and thus conserve different lines of variation. To escape floods, for example, some individuals of a species may learn to climb trees, while others learn to swim. This has been recognized in Gulick's Change of Habits as a cause of segregation (cf. ISOLATION) and thus of divergent evolution.

(4) In cases of apparent permanent influence, upon a stock, of temporary changes of environment, such as transplantation: the direction of variation seems to be changed by the temporary environment, when there is really only the temporary indirect selection of variations appropriate to the changed environment. For example, it is possible that plants undergo quick changes by indirect selection when transplanted, the effects of this selection of variations continuing a longer or shorter period after return to the original conditions of life, especially when the original environment does not demand their prompt weeding out. This is one of the cases most often cited as favouring the hypothesis of Lamarckian inheritance. (Osborn, however, thinks there is not enough time in these cases for the operation of organic selection.)

(5) In all cases of conscious or intelligent, including social, accommodation. In these cases conscious action directly reinforces and supplements congenital endowment at the same time that there is indirect selection of the variations which intelligence finds most suited to its needs. Thus congenital tendencies and predispositions are fostered. The influence of orthoplastic family life is well illustrated by Headley (as cited below). This is seen also in the rise of many instincts, for the performance of which intelligent direction has gradually become unnecessary; see the use of the principle in an independent way by P. Marchal (Rev. Scient., Nov. 21, 1896, 653), to explain the origin of the queen bee. See INSTINCT.

Indirect selection applies also to the origin of the forms of emotional expression (e.g. Darwin's classical case of the inherited fear of man by certain birds in the Oceanic Islands: cf. Darwin, Descent of Man, chap. ii), which are thought to have been useful and, in most cases, intelligent accommodations to an environment consisting of other animals. In man also we find reactions, e.g. of bashfulness, shame, &c., largely organic, whose origin it is difficult to explain in any other way, unless we admit the inheritance of acquired characters. It is also recognized that social action by animals (e.g. the more or less intelligent herding) was often of direct utility and caused their survival until the corresponding instincts became fixed.

It also works another way, as Groos shows: an instinct is broken up and so yields to the intelligent performance of the same function, by variation towards the increased plasticity and 'educability' which intelligent action requires. In this way another objection to Darwinism is met -- that which cites the difficulty of securing the modification and decay of instincts by natural selection alone.

(6) In this connection it has also been pointed out that with the rise of intelligence, broadly understood, there comes into existence an animal TRADITION (q.v.) -- treated also in the literature under the names 'social heredity,' 'imitation,' &c. -- into which the young are educated in each succeeding generation. This sets the direction of most useful attainment, and constitutes a new and higher environment. It is with reference to this, in many cases at least, that instincts both rise and decay: decay, when plasticity and continued relearning by each generation are demanded; rise, when fixed organic reactions stereotyped by variation are of most use. So there is constant adjustment, as the conditions of life may demand, between the intelligent actions embodied in tradition, and the instinctive actions embodied, through natural selection, in inherited structure; and this is the essential co-operation of the two factors, accommodation and variation, as postulated by the theory of organic selection. The line of acquired accommodations takes the lead -- variations follow. This is very different from the view which relies exclusively upon the natural selection of useful variations in this or that character; for it introduces a conserving and regulating factor -- a 'blanket utility,' so to speak -- under which various minor adaptations may be adjusted in the organism as a whole. Of course, the selection of the plasticity, required by intelligence and educability, is by direct natural selection; but, inside of this, the relation of the intelligence to the specific organic characters and functions is the one of 'concurrence' which organic selection postulates.

(7) It is a factor of stability and persistence of type as opposed, e.g., to the fatal result of disadvantageous variations (Wallace); since the individual accommodations may compensate in a constantly increasing way for the loss of direct utility of the character in question. This is notably the case with intelligent accommodations. These piece-out obstructed, distorted, or partial instincts or other functions, and modify the environment to secure their free play or to negative their disadvantageous results. This carries further the advantage which Weismann (Romanes Lecture) has claimed for INTRASELECTION (q.v., and see below).

(8) It secures the effectiveness of variation in certain lines, not only by keeping alive these variations from generation to generation, but also by increasing the number of individuals having these variations in common, until they become established in the species. It thus answers the stock objection to natural selection (cf. e.g. Henslow, Natural Science, vi, 1895, 585 ff., and viii, 1897, 169 ff.) which claims that the same variation would not occur at any one time in a sufficient number of individuals to establish itself, except in cases of great environmental change or of migration (cf. MUTATION). Organic selection shifts the mean of a character, and this changed mean is what natural selection requires (cf. Baldwin, Amer. Natural., as cited below, and Conn, The Method of Evolution, 75 f.).

(9) It is a segregating or isolating factor, as is illustrated under (3) above. Animals which make common accommodations survive and mate together. In the presence of an enemy, those animals of a group which can run fast escape together; those which can go through small holes remain likewise together; and so do those hardy enough to fight.

As to the possible universal application of organic selection, it would seem to depend upon whether there are any cases of congenital characters maturing without some individual accommodation due to the action of the life conditions upon their plastic material. Certain recent writers (Driesch, Delage, Ortmann) deny that any characters are entirely congenital, or 'congenital' at all in the current sense of the term which contrasts them with 'acquired' characters (cf. ACQUIRED AND CONGENITAL CHARACTERS). It would follow that in all cases those variations in which the most fortunate combination of innate and acquired elements is secured would survive under natural selection; and this would mean that organic selection is universal. In the words of Groos (Play of Man, Eng. trans., 373), 'organic selection may possibly be applied to all cases of adaptation (Anpassung)'; the question remains, therefore, in determining the scope of the principle, whether there are any characters which are not in some measure acquired in the individual's development.

This point of view follows naturally from the position taken by the school of so-called organicists (see Delage, Structure du Protoplasma, &c., 720), who insist in various ways upon the part played by the organism itself in evolution. The writers of this school, however, either hold to Lamarckian inheritance (Eimer), to a form of self-development (Driesch; called 'auto-régulation' and 'auto-détermination' by Delage), or to INTRA-SELECTION considered as repeating its results anew in each generation (Roux, Delage). In the exposition of this last view, Delage used the term 'sélection organique' for intra-selection (loc. cit., 725, 732); and Weismann (Romanes Lecture) combines intraselection, which 'effects the special adaptation of the tissues . . . in each individual' ('for in each individual the necessary adaptation will be temporarily accomplished by intraselection'), with his hypothesis of GERMINAL SELECTION (q.v.). 'As the primary variations,' says Weismann, 'in the phyletic metamorphosis occurred little by little, the secondary adaptations would probably, as a rule, be able to keep pace with them. Time would thus be gained till, in the course of generations, by constant selection of those germs the primary constituents of which are best fitted to one another, . . . a definite metamorphosis of the species involving all the parts of the organism may occur.' In this passage (which has been quoted by Osborn and others to show that Weismann anticipated the principle of organic selection) Weismann recognizes the essential co-operation of variation and modification which organic selection postulates, but he reverses the order of these factors by making germinal variations (in the words italicized above by the present writer) the leading agency in the determination of the course of evolution, while individual accommodation and modification 'probably keep pace with them' (the primary variations). The writers mentioned above, however, who originally expounded organic selection, rely upon 'coincident' variation to 'keep pace,' under the action of natural selection, with individual accommodation; which last thus takes the lead and marks out the course of evolution. The hypothesis of germinal selection, which is essential to Weismann's view, is not at all involved in theirs. In the words of Lloyd Morgan, who indicates substantially the relation between Weismann's views and his own as that given above: 'Natural selection would work along the lines laid down for it by adaptive modifications. Modification would lead; variation follow in its wake. Weismann's germinal selection, if a vera causa, would be a co-operating factor and assist in producing the requisite variations' (Habit and Instinct, 318). Defrance says on the same point (Année Biol., iii, 1899, 533): 'He (Weismann) has made use of his personal hypotheses on germ-plasm which are not universally admitted, while the conception of Ll. Morgan and Baldwin avoids this stumbling-block by not closing inquiry into the processes which enter into play. It is true that this leaves it an hypothesis; but it is nevertheless true that it offers an intelligible solution of one of those problems which appear on the surface to constitute the most insoluble of enigmas.' Osborn brings into play the further factor of 'determinate variation,' which if true would be analogous in its rôle to Weismann's germinal selection (see Osborn, On the Limits of Organic Selection, as below). He also holds that 'there is an unknown factor in evolution yet to be discovered.'

Literature: LL. MORGAN, Science, Nov. 27, 1896, and Habit and

Instinct (1896); OSBORN, Science, Apr. 3, 1896, and Nov. 27, 1896; and

On the Limits of Organic Selection, Science, Oct. 15, 1897; BALDWIN, Ment.

Devel. in the Child and the Race (1st ed., 1895, where the term organic

selection was first used; much developed in the Fr. and Ger. trans.); Science,

Mar. 20, 1896; and Amer. Natural., June and July, 1896; BALDWIN (in collaboration

with MORGAN and OSBORN), on the terminology of the subject, in Nature,

1v. (1897) 558, and Science, Apr. 25, 1897 (trans. in Biol. Centralbl.,

June 1, 1897, and in Rev. Scient., June, 1897); POULTON, Science, Oct.

15, 1897; WALLACE (review of Morgan), Natural Sci., x. 161; GROOS, The

Play of Man, 372 f., 376, 283, 395 (Eng. trans.); WHITMAN, Woods Holl Biol.

Lectures, 1898 (1899); THOMSON, The Study of Animal Life (1900); expositions

and criticisms are to be found (Index, sub verbo) in the Année Biol.

(literature for 1896 ff.). Late works in which the principle is adopted

are LL. MORGAN, Animal Behaviour (1900); CONN, The Method of Evolution

(1901); HEADLEY, The Problem of Evolution (1901; gives interesting cases

from nature). Cf. also GULICK, in Nature, Apr. 1, 1897; and see the recent

literature of INSTINCT. (J.M.B., C.LL.M.,

E.B.P., G.F.S.,

K.G.)

Organic Sensation: Ger. Organenpfindung; Fr. sensation interne; Ital. sensazione organica (or diffusa). A sensation whose adequate stimulus is a change in the state of a bodily organ, i.e. a physiological (as contradistinguished from a physical) process.

The organic sensations fall, so far as they are known, into the following groups: --

1) MUSCULAR SENSATION (q.v.): sensations from muscle, tendon, joint.

(2) Alimentary sensations: hunger, thirst, nausea.

(3) Sexual sensation: a single, unnamed quality.

(4) STATIC SENSATION (q.v.): dizziness. To these may perhaps be added the following: --

(5) Respiratory sensations (distinct qualities doubtful).

(6) Circulatory sensations: 'pins and needles,' itching (possibly), tingling, &c., arising from conditions of the blood-circulation, which may contain a specific quality.

The organic sensations are psychologically important (a) for the theory of feeling and emotion (James-Lange theory), and (b) for the theory of recognition and memory (Külpe's recognitive mood, Ribot's affective memory, &c.). Cf. COMMON SENSATION. It may be noted that the obscurity of the organic qualities is the reason for, and partial justification of, a 'functional' classification of SENSATION (q.v.).

Literature: MACH, Bewegungsempfindungen (1875); RICHET, Recherches

expér. et clin. sur la sensibilité (1877); KRÖNER, Körperliches

Gefühl (1887); KÜLPE, Outlines of Psychol., 140; WUNDT, Physiol.

Psychol. (4th ed.), i. 284; HAMILTON, Lects. on Met., ii. 154 ff.; BEAUNIS,

Les sensations internes; TH. RIBOT, Maladies de la personnalité

(1888); Psychol. des sentiments (1896). (E.B.T.)

Organism [Gr. organon, an organ]: Ger. Organismus; Fr. organisme; Ital. organismo. (1) A living being: see the following topic. (2) A totality whose various parts or elements are related to each other according to some principle which is derived from the whole itself, and hence is internal and not external, necessary and not accidental. A system. Cf. ORGANIC.

While the Greeks use the term in quite another sense from the moderns, the idea, even in its generalized philosophical use, was quite familiar to them. Plato regarded the world as an animated whole -- as zwon. With Aristotle the end or form animates all potentiality or matter in such a way as to keep it moving towards perfection, and thereby gives it order. In living beings, this appears in the continual higher stages of articulation (diarqrwsiV). Thus the form is the inner life of nature, as distinct from an external arrangement. In this sense, Aristotle applies the notion (not the term) organism, or a whole ordered and moving from an internal principle of causality, to the state, since the individual gets his social life only through his immanent connection with the whole. The Stoics expressly declare the world to be ousthma, a living organized whole; and ethically they proclaim that the individual is not a part (meroV), but a member (meloV) of the universe. The conception on the social side passed into Christianity in the conception of the Church as the mystic body (corpus mysticum) of Christ. In the middle ages, the paralleling of the state and the living body is common, and John of Salisbury undertakes to find a part of the body corresponding to every part of the state (see Eucken, Grundbegriffe d. Gegenwart, 157). Herder, in the 18th century, is most active in reviving a conception of nature as a living whole, working according to an internal principle, through a continuous series of manifestations. Kant gives the conception a clear-cut definition (see ORGANIC), but gives the idea only a subjective validity. Schelling, however, gives the term a completely objective meaning, applicable to the universe itself. Through his followers it becomes a favourite term to designate the principle of philosophies which regard the world as moving from intrinsic principles, and as producing its effects after the manner of an immanent life and intelligence (Syst. d. trans. Idealismus, 261).

Spencer has recently used the term in a generalized sense in recent English thought, as in his assertion that society is an organism. On discussions on this point, however, there is ambiguity -- organism is sometimes used as analogous to the organs (or functions) of an animal body; at other times, in its logical sense, of a coherent whole, systematized by an internal principle. Cf. SOCIAL ORGANISM.

Literature: see ORGANIC, and SOCIAL ORGANISM. (J.D.)

Organism (in biology). A

discrete body, of which the essential constituent is living protoplasm.

The term originally indicated the recognition of organization as essential

to life, and as opposite to unorganized or dead matter. Cf. LIFE, and LIVING

MATTER. (C.S.M.)

Organization: Ger. Organisation; Fr. organisation; Ital. organizzazione. A more or less systematic arrangement of relatively separate parts in a whole suited to fulfil any sort of function.

The term has applications, with varying degrees of definiteness, in the phrases 'mental organization' (in which the systematic determination of the flow of the mental life is characterized), SOCIAL ORGANIZATION (q.v.), 'organization of knowledge' (the adjustment, in a philosophical view, of the details of knowledge as contributed by the different sciences).

The shading of meaning which distinguishes organization from ORGANISM (q.v.) is in the direction of relative looseness of relation as between the parts and the whole, and relative lack of independence of conditions external to the system. An organization is 'formed,' 'controlled,' 'modified,' 'worked,' &c.; to an organism these predicates are not applicable. Moreover, we do not speak of the 'organs' of an organization, but of its 'members'; each being at once less dependent upon the whole, and less necessary to it. Hence the preference for 'mental organization'; it leaves open the question whether mind has the inherent principle of its own systematic process which is necessary to an organism.

In the adjective organic this difference disappears, and much ambiguity

arises therefrom. The term 'organized' is preferable to characterize an

organization, organic being limited in its application to organisms proper.

(J.M.B.)

Organization (industrial): Ger. Unternehmungsform; Fr. organisation industrielle; Ital. ordinamento industriale. The immaterial advantage for production which have attended the growth of capital.

Reckoned by Walker and Marshall as an agent or factor in production,

co-ordinate with land, labour, and capital. (A.T.H.)

Organon [Gr.]: the same in the other languages. Since neither the Aristotelian definition of a speculative science, nor of a practical science, nor of an art, seemed to suit logic very well, the early peripatetics and commentators denied that it was either a science or an art, and called it an instrument, organon; but they did not precisely define their meaning. It was negative chiefly. The collection of Aristotle's logical treatises, when it was made, thus came to be called the Organon.

Francis Bacon, disapproving of Aristotle's methods, wished all that

to be laid aside; and he consequently called his work, which was designed

to be a guide for establishing a systematic inductive procedure, Novum

Organum. The name was afterwards imitated by sundry authors, as Lambert

in his Neues Organon, and Whewell in his Novum Organum Renovatum.

(C.S.P.)

Oriental Philosophy (and

Religion).

Orientation (bodily) [Lat. orientare, to set up with regard to the cardinal points, especially the east]: Ger. Orientirung; Fr. orientation; Ital. orientazione. (1) The maintenance of the normal position and spacial relationships of the body, as a whole, with reference to its surroundings. A better term for this meaning is equilibrium.

(2) The undisturbed consciousness of the spacial relationships of the body, as a whole, to its surroundings. (J.M.B.)

The orientation of the organism in space is conditioned psychologically by a number of sense and reflex factors, by sensations of vision, by sensations from skin, joints, muscles of limbs and trunk, muscles of eyes, by the visual and tactual reflexes, and by the sensory and reflex mechanism of the STATIC SENSE (q.v.). (E.B.T.)

While accomplished by a fused mass of these sensations orientation becomes

largely reflex, and only intrudes itself into consciousness when disturbed,

as when one is very sleepy or under the influence of drugs. The balancing

of the head, for example, is quite subconscious; yet when we nod, we discover

certain elements of sensation, e.g. from the muscles co-ordinated with

those of vision by which the normal head position is maintained. This head-balancing

is gradually acquired by the child, as is also the erect position of the

whole body, through association, together with natural reflexes. The influence

of vision, normal and under artificial conditions, has been investigated

experimentally by Stratton (Psychol. Rev., iv., 1897, 341,

463). (J.M.B.)

Orientation (mental). The normal ability to recognize one's surroundings and the personal and social relations of the environment.

In mental disorders this power is frequently lost; the patient no longer

recognizes or realizes his condition, his whereabouts, or his departure

from his usual life. This condition is marked in insanities accompanied

by hallucinations and systematic delusions. It is also characteristic of

delirium, and of various forms of intoxication. (J.J.)

Orientation (illusions of): Ger. Orientirungstäuschung; Fr. renversement de l'orientation (Binet); Ital. illusione dell' orientazione. Disturbance of the normal consciousness of direction, especially as involving the shifting of the points of the compass in a way which shifts the entire physical environment with reference to the observer, but does not disturb the spacial relationships of objects to one another.

The term illusions of orientation was suggested by the translator of

Binet's standard paper on the subject (Psychol. Rev., i).

Such shifting of the physical world is usually either 180o or

90o exactly; rarely between them or under 90o. Information

does not usually dispel the illusion, which persists as a consistent scheme

of directions, even after the true scheme is reinstated. For details, cases,

and literature, see the paper by Binet, cited above. (J.M.B.)

Orientation (law of constant) [Ger. Gesetz or Prinzip) der constanten Orientirung; Fr. loi d'orientation constante; Ital. legge di orientazione costante. This law declares that the orientation of the eye is constant for every recurrent position of the line of sight, no matter by what road the line (or the eye) has travelled. It was formulated by Donders in 1847: see DONDERS' LAW.

Literature: HELMHOLTZ, Physiol. Optik (2nd ed.), 619, 638; HERING,

Beitr. z. Physiol., 248; WUNDT, Physiol. Psychol. (4th ed.), ii. 119. (E.B.T.)

Origen, surnamed Adamantios. (185-254

A.D.) His early education was at the hands of his father, Leonides, and

Clemens Alexandrinus. At his father's martyrdom, Origen opened a school.

He was made master of the catechetical school of Alexandria by Bishop Demetrius.

Studied philosophy (under Ammonius Saccas) and Hebrew (upon a visit to

Rome). Called to Greece (228) to dispute a heresy, and was made a presbyter

at Caesarea. This ordination Bishop Demetrius refused to recognize. Excommunicated,

231, he opened his school in Caesarea with still greater success than before.

See ALEXANDRIAN SCHOOL, and PATRISTIC PHILOSOPHY (5).

Origin of Evil: see equivalents for EVIL, under that term. A phrase used in discussions of the genesis and nature of EVIL (q.v.) in its various meanings, especially ethical evil.

The term THEODICY (q.v.) has come into use to include this problem in a larger one, more especially when treated in a larger one, more especially when treated from a theistic and apologetic point of view. A preliminary problem is necessarily that of the definition and classification of evils, and much of the discussion is vitiated by lack of clearness on this point. See EVIL.

Literature: the Book of Job, and the literature pertaining to

Job, of which a late discussion is by ROYCE, Studies in Good and Evil.

A different metaphysical standpoint is represented by ORMOND, Basal Concepts

in Philosophy. For more theological treatment see the general works cited

under THEOLOGY. As a problem of the philosophy of RELIGION (q.v.), it is

treated in most of the literature there cited. See also THEODICY, especially

the work of LEIBNITZ. (J.M.B.)

Origin of Life: Ger. Ursprung des Lebens; Fr. origine de la vie; Ital. origine della vita. The source of the first living organism upon the earth.

The attempt to prove spontaneous generation having failed, other theories have been advanced. It was suggested by H.E. Richter (1865), and later by Helmholtz and Lord Kelvin, that micro-organisms might reach the earth upon meteorites. There are no direct observations to support this suggestion, which does not explain the origin of life, but merely puts it one stage further off. (C.S.M.)

At the present time life is known only in organisms of complex structure and chemical constitution, and always accompanied by the presence of a substance called protoplasm, to the activities of which all vital phenomena are due. Since the crude theory of the spontaneous generation of such organisms has been disposed of, there remains only, as a scientific explanation, the theory of their gradual evolution from inorganic lifeless elements, at a time when the earth had cooled sufficiently to allow the necessary chemical combinations to take place. The determination of the series of increasingly complex bodies, which must have formed links in the long chain of development leading up to the formation of the proteids of which living protoplasm now consists, has been attempted by many observers, and not entirely without success. Amongst these may be especially mentioned Pflüger. Cf. LIFE, LIVING MATTER, PROTOPLASM, and VITALISM.

Literature: E. PFLÜGER, Pflüger's Arch. (1875); T.

H. HUXLEY, The Physical Basis of Life (1868), and Collected Essays; M.

VERWORN, Gen. Physiol. (1899). (E.S.G.)

Origin of Species: Ger. Ursprung der Arten; Fr. origine des espèces; Ital. origine delle specie. Theory of the rise of diversities in the forms of animal life of sufficient magnitude to constitute different SPECIES (q.v.).

The phrase has been classic since the appearance of Darwin's Origin

of Species by Means of Natural Selection. The two great rival theories

are SPECIAL CREATION and EVOLUTION; see those topics. The corresponding

'classics' of the special creation theory are the Book of Genesis

and its poetical exposition in Milton's Paradise Lost. Also see

FACTORS OF EVOLUTION, DESCENT, HEREDITY, TELEOLOGY, and NATURAL SELECTION.

(J.M.B., E.B.P.)

Origin versus Nature: no concise foreign equivalents. A phrase used to indicate the question whether a complete account of the origin of a thing would also be a complete account of its nature.

The inquiry is often made under the terms origin versus reality,' or, in an expression a little more sharp in its epistemological meaning, 'origin versus validity.' 'Origin versus nature' seems to mark better the general distinction between the 'how' of the question -- how a thing arose or came to be what it is; and the 'what' of the question -- what a thing is.

The problem is brought to the fore by the current view that the nature -- 'the what' -- of a thing is given in, and only in, its behavior, i.e., in the processes or changes through which it passes. The more we know of behaviour of a certain kind, then the more we know of reality, or of the reality, at least, which that kind of behavior is. And it is evident that we may know more of behaviour in two ways. We may know more of behaviour because we take in more of it at once; this depends on the basis of knowledge we already have -- the relative advance of science in description, explanation, &c., upon which our interpretation of the behaviour before us rests. In the behaviour of a bird which flits before him a child sees only a bright object in motion; that is the 'thing' to him. But when the bird flits before a naturalist, he sees a thing whose behaviour exhausts about all that is known of the natural sciences.

When we come further, on this view, to approach a new thing, we endeavour, in order to know what it is, to find out what it is doing, or what it can do in any artificial circumstances which we may devise. Just so far as it does nothing, or so far as we are unable to get it to do anything, just so far we confess ignorance of what it is. We can neither summon to the understanding of it what we have found out about the behaviour of other things, nor can we make a new class of realities or things to put it in. All analysis is, therefore, just the finding out of the different centres of behaviour which a whole given outburst of reality includes.

Yet there is a second aspect of a thing's reality which is just as important. Behaviour means, in some way, change. A mere lump would remain a lump, and never become a thing, if, to adhere to our phenomenal way of speaking, it did not pass through a series of changes. A thing must have a career; and the length of its career is of immediate interest. We get to know the thing not only by the amount of its behaviour, secured by examining a cross-section, so to speak, but also by the increase in the number of these sections which we are able to secure. The successive stages of behaviour are necessary in order really to see what the behaviour is. This fact underlies the whole series of determinations which ordinarily characterize things, such as cause, change, growth, development, &c., and which are denoted by the terms 'dynamic,' 'genetic,' &c.

The strict adherence to the definition of a thing in terms of behaviour, therefore, would seem to require that we should wait for the changes in any case to go through a part at least of their progress -- for the career to be unrolled, that is, at least in part. Immediate description gives, so far as it is truly immediate, no science, no real thing with any richness of content; it gives merely the snap-object of the child. And if this is true of science, of every-day knowledge of things, which we live by, how much more of the complete knowledge of things desiderated by philosophy as an answer to the question, What? It would be an interesting task to show that each general aspect of the 'what' in nature has arisen upon just such an interpretation of the salient aspects presented in the career of individual things.

A second point in regard to the 'what,' therefore, is that any 'what' whatever is in large measure made up of judgments based upon experiences of the 'how.' The fundamental concepts of philosophy reflect these categories of origin, both in their application to individuals -- to 'mere things' -- and also in the interpretation which they have a right to claim; for they are our mental ways of dealing with what is 'mere' on one hand and of reaching the final reading of reality which philosophy makes its method. Of course the question may be asked: How far origin? That is, how far back in the career of the thing is it necessary to go to call the halting-place 'origin'? This we may well return to lower down; the point here is that origin is always a reading of part of the very career which is the content of the concept of the nature of the thing.

Coming now closer to particular instances of the 'what,' and selecting the most refractory case that there is in the world, let us ask these questions concerning the mind. This case may be taken because, in the first place, it is the urgently pressing case; and, second, because it is the case in which there seems to be, if anywhere, a gaping distinction between the 'what' and the 'how.' Modern evolution claims to discuss the 'how' only, not to concern itself with the 'what'; or, again, it claims to solve the 'what' entirely by its theory of the 'how.' To these claims, what shall we say in the case of mind?

From the point of view given above, it would seem that the nature of mind is its behaviour generalized; and, further, that this generalization necessarily implicates more or less of the history of mind; that is, more or less of the career which discloses the 'how' of mind. But a striking fact comes up immediately, when we begin to consider mental, and with it biological, reality -- the fact of growth, or, to put it on its widest footing, the fact of organization. The changes in the external world which constitute the career of a thing, and so show forth its claim to be considered a thing, fall under some very wide generalizations, such as those of chemistry, mechanics, &c.; and when the examination of the thing's behaviour has secured its description under these principles in a pretty exhaustive way, we say the thing is understood. But the things of life, and the series of so-called organic changes which unroll its career, are not yet so broadly statable. When we come to mind, again, we find, indeed, certain well made out generalizations of its behaviour. But here, as in the case of life, the men who know most have not a shadow of the complacency with which the physicist and the chemist categorize their material. It is for this reason, no doubt, in part, that the difference between the two cases gets its emphasis, and the antithesis between origin and nature seems so necessary in one case, while it is seldom raised in the other. For who ever heard a student of natural science say that the resolution of a chemical compound into its elements, thus demonstrating the components and the law of the origin of the 'thing' analysed, did not solve the question of its nature, so far as science can state a solution of that question?

But we cannot say that the whole difference is one of greater modesty on the part of the psychologists. The facts rather account for their modesty. And the prime fact is one formulated in more or less obscurity by many men, beginning with Aristotle: the fact, namely, that organization, considered as itself a category of reality, never reaches universal statement in experience. To confine the case at first to vital phenomena, we may say that to subsume a plan or animal under the category of organization is to make it at once to a degree an unknown quantity, an X: a form of reality which, by right of this very subsumption, predicts for itself a phase of behaviour as yet unaccomplished -- gives a prophecy of further career, but gives no prophecy (apart from other information which we may have) of the nature of this further phase of career, in kind. Every vital organization has part of its career yet to run. If it has no further career yet to run, it is no longer an organization: it is then dead. Its reality is then exhausted by the predication of the categories of chemistry, mechanics, &c. -- the sciences which construe all careers retrospectively. A factor of the biological and mental categories alike is, on the contrary, just this element of what the present writer has elsewhere called the 'Prospective Reference' (Ment. Devel. in the Child and the Race, chaps. vii, xi).

It does not matter how the content in any particular filling up of the category may be construed after it takes on the form of accomplished fact -- after, i.e., it becomes a matter of 'retrospection.' All constructions in terms of content mean the substitution of the retrospective categories for those of 'prospection'; that is, it is the construction of an organization after it is dead, or -- what amounts to the same thing -- by analogy with other organizations which have run down or have died, in our experience. Suppose, for example, we take the construction of the category of accommodation, in each particular instance of it, in terms of the law of FUNCTIONAL SELECTION (q.v.), and so get a statement of how an organism actually acquires any one of the special adaptations of its mature personal life; what, then, have we done? It seems evident that we have simply resorted to the 'retrospective' reference; we have changed our category in the attempt to get a concrete filling for a particular event; we are interpreting it as already having happened. To adopt the view that the category of organization can be in every case filled up with matter in this way, does not in any sense destroy the prospective element in the category of organization; for the psychological subtlety still remains in mind in the doing of it, either that the event must still be awaited to determine the outcome, and that I am agreeing with myself and my scientific friends to wait for it, or that we are solving this case by others for which some one has waited. A good instance of our mental subtleties in such cases is seen in the way we use the category of POTENTIALITY (q.v.). The extreme case of the reduction of the categories of prospective reference to those of retrospection is evidently the formula for PROBABILITY (q.v.). That formula appears to be a category of retrospection, applied to material which does not admit of any narrower or more special retrospective formulation.

The inference from this is that our predicate 'reality' is not adequately expressed, in certain cases -- cases of vital and psychological organization -- in terms of the experienced behaviour of so-called real content. The very experience on the basis of which we are wont to predicate reality testifies to its own inadequacy. We seem to be shut up to the alternatives that either the notion of reality does not rest upon experiences of behaviour, or that the problematic judgments based upon those experiences of progressive organization which we know currently under the term development are as fundamental to these kinds of reality as are those more static judgments based on history or origin.

It may be well, in view of the importance of this conclusion, to see something more of its bearings in philosophy. The historical theories of design, or TELEOLOGY (q.v.) in nature, have involved this question. Those familiar with the details of the design arguments pro and con will not need to have brought to mind the confusion which has arisen from the mixing up of the 'prospective' and 'retrospective' points of view. Design, to the mind of many of the older theistic writers, was based upon relative unpredictability -- or better, infinite improbability. Such an argument looks forward: it is reasoning in the category of organization, and under the prospective reference. The organization called mental must be appealed to. What, was asked, is the probability of the letters of the Iliad falling together so as to spell out the Iliad? Their opponents, on the other hand, have said: Why is not the Iliad combination as natural as any other? -- one combination has to happen; what is to prevent this? If a child who cannot read should throw the letters, the Iliad combination would be no more strange to him than any other. These men are reasoning in the retrospective categories. They are interpreting facts. The fault of the latter position is that it fails to see in reality the element of organization which the whole series when looked at from the antecedent point of view of the production of the real Iliad requires. It is true that the Iliad is one of an infinite number of possible combinations; but it is also true that Homer did not try the other combinations before hitting upon the Iliad. What would really happen, further, if the child should throw the Iliad combination, would be that nature had produced a second time a combination once before produced without other trials (in the mind of Homer, and through him in ours), and it is the correspondence of the two -- apart from the meaning of the text of the Iliad, i.e. its original production -- which would surprise us. But this added element of organization needed to bring nature into accord with thought, and which the postulate of design makes in reaching a designer -- this is not needed for the mere historical or retrospective interpretation of the facts. In other words, if the opponents of design are right in holding to a complete reduction of organization to retrospective categories, they ought to be able to produce intelligible results by throwing a multiple of twenty-six dice each marked with a letter of the alphabet. They of course cannot; but that does not make it necessary to deny the absolute universality of the retrospective categories: for after the Iliad is produced it may be considered one of an infinite number of possible combinations, happening in accordance with the law of PROBABILITY (q.v., especially the criticism of 'inverse' probability).

The later arguments for design, therefore, which tend to identify it with future organization, and to see in it, so far as it differs from natural law, simply a harking forward to that career of things which is not yet unrolled, but will be in accordance with thought -- yet which, when completely unrolled, will still be a part of the final statement of origins in terms of natural law -- this general view has so much justification.

Further, it is clear that the two opposed views of adaptation in nature are both genetic views -- instead of being, as is sometimes thought, one genetic (that view which interprets the adaptation after it has occurred) and the other analytic or intuitive (that view which seeks a beforehand construction of design). The former of these is usually accredited to the evolution theory; and properly so, seeing that the evolutionist constantly looks backward. But the other view, the design view, is equally genetic. For the category of organization by which it proceeds is also distinctly an outcome of the movement or drift of experience towards the realization of career. Teleology, then, when brought to its stronghold, is a genetic outcome, and owes what force it has to the very point of view that its most fervent advocates -- especially its theological advocates -- are in the habit of running down. The consideration of the stream of genetic history itself, no less than the attempt to explain the progress of the world as a whole, its career, leads us to admit that the real need of thinking about the future in terms of organization is as great as the need of thinking about the past in terms of natural law. The need of mental organization or design is found in the inadequacy of natural law to explain the further career of the world -- and its past career also, as soon as we go back to any place in the past which then becomes future. It would be possible, also, to take up this last remark for further thought, and to make out a case for the proposition that the categories of 'restrospective' thinking also involve a strain of organization - a proposition which is equivalent to one which the idealists are forcibly urging from other grounds and from another point of view. Lotze's argument to an organization at the bottom of natural causation has lost nothing of its power. Ormond (Foundations of Knowledge) has given us an argument for a social interpretation of physical interaction. It is hard to see the force of the assumption tacitly made by the positivists, and as tacitly admitted by their antagonists, that causation, viewed as a category of experience, is to be ultimately understood entirely under such restrospective constructions as 'conservation of energy,' &c. Such constructions involve an endless retrospective series. And that is to say that the problem of origin is finally insoluble. Well, so it may be. But yet one may ask, why this emphasis of the 'retrospective' -- a category which has arisen with just the basis of experience that the 'prospective' also has? It may be a matter of taste; it may be a matter of 'original sin.' But if we go on to try to unite our categories of experience in some kind of a broader logical category, then the notion of the ultimate, it would seem, must require -- and somehow combine -- both of the aspects which our conception of reality includes; the 'prospective' no less than the 'retrospective.' Origins must take place continually as truly as much sufficient reasons. The only way to avoid this is to say that reality has neither forward nor backward reference. So say the idealists who find in 'thought' a punctum stans which is not in time. But in dealing with reality we are dealing with experience; and the opinion has some force that thought which looks neither backwards nor forwards -- whatever further category it may have under which the antithesis may be transcended -- is not thought at all.

Another subtlety might raise its head in the inquiry whether in their origin all the categories themselves did not have a 'natural history.' If so, it might be said, we are bound, in the very fact of thinking at all, to give exclusive recognition to the historical aspect of reality. But here is just the question: does the outcome of career to date give exhaustive statement of the idea of the career as a whole? There would seem to be two valid objections to it. First, it would be, even from the strictly objective point of view, the point of view of physical science, to construe the thing mind entirely in terms of the behaviour of its stages antecedent to the present: that is, entirely in terms of descriptive content, by use of the categories of retrospective interpretation. And, second, it does not follow that because a mental way of regarding the world, i.e. the way of prospection, is itself a genetic growth, therefore it is a misleading way, for the same might be urged against the categories of descriptive science, i.e. the retrospective, which have had the same origin.

There are one or two points among many suggested by the foregoing which it may be well to refer to. It will be remembered that in speaking of the categories of organization as having prospective reference, instances were adduced largely drawn from the phenomena of life and mind, contrasting them somewhat strongly with those of chemistry, physics, &c. The use afterwards made of these categories now warrants us in turning upon that distinction, in order to see whether our main results hold for the aspects of reality with which those sciences deal as well. It was intimated above in passing that the other categories of reality, such as causation and mechanism, are really capable of a similar evaluation as that given to teleology. This possibility may be put in a little stronger light.

It is evident, when we come to think of it, that all organization in the world must rest ultimately on the same basis; and the recognition of this is the strength of thorough-going naturalism and absolute idealism alike. The justification of the view is to be made out, it would appear, by detailed investigation of the genetic development of the categories. The way the child reaches his notion of causation, for example, or that of personality, is evidence of the way we are to consider the great corresponding race-categories of thought to have been reached: and the category of causation is, equally with that of personality or that of design, a category or organization. The reason that causation is considered a cast-iron thing, implicit in nature in the form of 'conservation of energy,' &c., is that in the growth of the rubrics of thought certain great differentiations have been made in experience according to observed aspects of behaviour, and those events which exhibited the more definite, invariable aspects of behaviour have been put aside by themselves; not of course by a conscious convention of man's, but by the conventions of the organism working under the very method which we come -- when we make it consciously conventional -- to call this very category or organization. What is conservation but a kind of organization looked at retrospectively and conventionally? Does it not hold simply because my organism has made the convention that only that class of experiences which are 'objective' and regular and habitual to me shall be treated together, and shall be subject to such a regular mental construction on my part?

But the tendency to make all experience liable to this kind of causation is an attempt to undo nature's convention -- to accept one of her results, which exists only in view of a certain differentiation of the aspects of reality, and apply this universally to the subversion of the very differentiation on the basis of which it has arisen. The fact that there is a class of experiences whose behaviour issues in such a purely historical statement and arouses in me such a purely habitual attitude, is itself witness to a larger organization -- that of the richer consciousness of expectation, volition, and prophecy. Otherwise conservation could never have secured abstract statement in thought.

The reason that the category of causation has assumed its show of importance is just that which intuitionist thinkers urge; and a historical example of confusion due to their use of it may be used for illustration. Causation is about as universal a thing -- in its application to certain aspects of reality -- as could be desired. And we find men of this school using this fact to reach a certain statement of theism. But they then find a category of 'freedom' claiming the dignity of an intuition also; and although this comes directly in conflict with the uniformity ascribed to the other, nevertheless it also is used to support the same theistic conclusion. The two arguments read: (1) an intelligent God exists because the intelligence in the world must have an adequate cause, and (2) an intelligent God exists because the consciousness of freedom is sufficient evidence of a self-active intelligence in the world, which is not caused. All we have to say, in order to avoid the confusion, is that any mental fact is an 'intuition' in reference only to its own content of experience. Intelligence viewed as a natural fact, i.e. retrospectively, has a cause; but freedom in its meaning in reality, i.e. with its prospective outlook, as prophetic of novelties, is not adequately construed in terms of history. So both can be held to be valid, but only by denying universality to each 'intuition' and confining each to its sphere and peculiar reference in the make-up of reality.

Another thing to be referred to in this rough discussion concerns the more precise definition of 'origin.' How much of a thing's career belongs to its origin? How far back must we go to come to origin?

Up to this point the word has been used with a meaning which is very wide. Without trying to find a division of a thing's behaviour which distinguishes the present of it from its history, we have rather distinguished the two attitudes of mind engendered by the contemplation of a thing, i.e. the 'retrospective' attitude and the 'prospective' attitude. When we come to ask for any real division between origin and present existence, we have to ask what a thing's present value is. In answer to that, we have to say that its present value resides very largely in what we expect it to do; and then it occurs to us that what we expect it to do is no more or less than what it has done. So our idea of what is, as we said above, gets its content from what has been. But that is to inquire into its history, or to ask for a fuller or less full statement of its origin or career. So the question before us seems to resolve itself into the task of finding somewhere in a thing's history a line which divides its career up to the present into two parts -- one properly described as origin, and the other not. Now, on the view of the naturalist pure and simple, there can be no such line. For the attempt to construe a thing entirely in terms of history, entirely in the retrospective categories, would make it impossible for him to stop at any point and say, 'This far back is nature and further back is origin'; for at that point the question might be asked of him, 'What is the content of the career which describes the thing's origin?' -- and he would have to reply in exactly the same way he did if we asked him the same question regarding the thing's nature at that point. He would have to say that the origin of the thing observed later was described by career up to that point; and is not that exactly the reply he would give if we asked him what the thing was which then was? So to get any reply to the question of the origin of one thing different from that to the question of nature at an earlier stage, he would have to go still further back. But this would only repeat his difficulty. So he would never be able to distinguish between origin and nature except as different terms for describing different sections of one continuous series of aspects of behaviour. This dilemma holds also, I think, in the case of the intuitionist. For as far as he denies the natural history view of origins and so escapes the development above, he holds to special creation by an intelligent Deity; but to get content to his thought of Deity he resorts to what he knows of mental behaviour. The nature of mind then supplies the thought of the origin of mind.

Of course, on the view developed, the question of the ultimate origin of the universe may still come up for answer. Can there be an ultimate stopping-place anywhere in the career of the thing-world as a whole? Does not our position make it necessary that at any such stopping-place there should be some kind of filling drawn from yet antecedent history to give our statement of the conditions of origin any distinguishing character? It seems so. To say the contrary would be to do in favour of the prospective categories what we have been denying the right of the naturalist to do in favour of those of retrospect. Neither can proceed without the other. The only way to treat the problem of ultimate origin is not to ask it, as an isolated problem, but to reach a category which intrinsically resolves the opposition between the two phases of reality. Lotze says that the problem of philosophy is to inquire what reality is, not how it is made; and this will do if we remember that we must exhaust the empirical 'how' to get a notion of the empirical 'what,' and that there still remains over the 'prospect' which the same author has hit off in his famous saying: 'Reality is richer than thought.' To desiderate a what which has no how -- this seems as contradictory as to ask for a how in terms of what is not. It is really this last chase of the 'how' that Lotze deprecates -- and rightly.

Of the great historical solutions, that of the intellecutalists leans to the retrospective, that of the voluntarists to the prospective; a consistent affectivist theory has never been worked out, although something might be said for a form of what we may baptize beforehand as 'aesthonomic idealism' -- aesthetic experience being made the metaphysical prius both of science and of value. This would be no doubt as profitable as the Hegelian logicism which reads reality out of the categories in order to transcend their oppositions.

The conclusions may be summed up in certain tentative propositions as follows: --

(1) All statements of the nature of 'things' get their matter mainly from the processes which they have been known to pass through: that is, statements of nature are for the most part statements of origin.

(2) Statements of origin, however, never exhaust the reality of a thing, since such statements cannot be true to the experiences which they state unless they construe the reality not only as a thing which has had a career, but also as one which is about to have a career; for the expectation of the future career rests upon and is produced by the same historical series as the belief in the past career. Cf. PRAGMATISM, passim.

(3) All attempts to rule out prospective organization or teleology -- the belief in the correspondence between reality and thought -- from the world would be fatal to natural science, which has arisen by a series of provisional retrospective interpretations of just this kind of organization: and fatal also to the historical interpretation of the world found in the evolution hypothesis; for the category of teleology thus understood is but the prospective reading of the same series which, when read retrospectively, we call evolution. Cf. the remarks on teleology and evolution under HEREDITY.

(4) The fact that mental products, ideas, intuitions, &c., have a natural history is no argument against their validity or worth as having application beyond the details of their own history; since, if so, then a natural history series can issue in nothing new. But that is to deny the existence of the idea or product itself, for it is a new thing in the series in which it arises.

(5) All these points may be held together in a view which gives each mental content a twofold function in the mental life. Each such content begets two attitudes in the progressive development of the individual. So far as it fulfils earlier habits, it begets and confirms the historical or retrospective attitude; so far as it is not entirely exhausted in the channels of habit, it begets the expectant or prospective attitude.

(6) The final account of reality must invoke a category which in some way reconciles these two points of view.

Literature: RITCHIE, Darwin and Hegel, chap. i; ROYCE, Spirit

of Mod. Philos., in loc.; and Int. J. of Ethics, July, 1895; BALDWIN, Int.

J. of Ethics, Oct., 1895; The Origin of a Thing and its Nature, Psychol.

Rev., ii, 1895, 551 ff. (a paper which this article in part repeats); URBAN,

Psychol. Rev., iii, 1896, 73 ff. (J.M.B.)

Original: Ger. ursprünglich, originell; Fr. original; Ital. originale, originario. (1) Adjective of origin, meaning (a) primitive, (b) fundamental (original truth), (c) underived (original qualities, Locke). Cf. GENESIS.

(2) COPY (q.v., sense 1) or MODEL (q.v.).

(3) Applied also to that from which something originates: e.g. original

thinker, original source, &c. (J.M.B.)

Original Quality: see ORIGINAL

(1c), and QUALITY.

Original Sin: Ger. Erbsünde; Fr. péché originel; Ital. peccato originale. A natural tendency or disposition to evil in human nature which is ascribed to the fall of man and which tends inevitably to actual sin in the individual life. See SIN.

Original sin is related to total depravity as a concomitant effect of the fall of man. The great exponent of the doctrine among early thinkers is Augustine. It has been denied by Pelagians and Socinians. The dogma is one of the essential features of Calvinism.

Literature: JULIUS MÜLLER, Die christl. Lehre v. d. Sünde

(6th ed., 1877; Eng. trans. of same, Edinburgh, 1877); JONATHAN EDWARDS,

The Great Doctrine of Original Sin defended, ii (Worcester ed.). Works

on THEOLOGY (q.v.). (A.T.O.)

Orphic Literature: Ger. orphische Dichtungen; Fr. littérature orphique, les orphiques; Ital. letteratura orfica. A collection of poems and hymns ascribed to Orpheus, the mystic founder of a religious sect or school which arose in Greece during the 6th century B.C., but which were actually composed at different periods by a number of representatives of the sect.

Of Orpheus, who is celebrated both as a divine player on the lyre and as the poet founder of a religion, there is no trustworthy evidence (so Aristotle thinks) that he was a real personage. The doctrines of the sect are a compound of Bacchic mysteries and the philosophical tenets of the Pythagoreans. Except a few fragments which have been collected by Lobeck, and other verses found later and dating probably from the 3rd century B.C., the Orphic literature, which held a prominent place in the contests and religious mysteries of Greece, has been lost.

Literature: LOBECK, Aglaophamus (1829); ABEL, Orphica (Berlin,

1885); GRUPPE, Die griechischen Culte u. Mythen (Leipzig, 1887). (A.T.O.)

Orthodoxy (in theology) [Gr. orqoV, straight, + doxa, opinion]: Ger. Orthodoxie; Fr. orthodoxie; Ital. ortodossia. Correctness of belief as determined by the authoritative symbols of an ecclesiastical organization, in the light of some accepted interpretation.

The notion of orthodoxy presupposes some ultimate court of appeal. On this there is no general agreement among Christians. Roman Catholics find the ultimate test or orthodoxy in the deliverance of an infallible pope or an infallible church, while Protestants as a rule make the final appeal to Scripture. This, however, is not strictly final, as some interpretation of Scripture must be accepted as standard. Orthodoxy is a purely relative term, and always presupposes an attitude of conformity to an accepted standard of belief.

Literature: SHEDD, Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy (1893); NEWMAN SMYTH,

The Orthodox Theol. (1883). (A.T.O.)

Orthogenesis [Gr. orqoV, straight, + genesiV, origin]: Ger. Orthogenesis; Fr. orthogénèse, évolution orientée; Ital. ortogenesi. Evolution which is definitely directed or DETERMINATE (q.v.) by reason of the nature or principle of life itself. Cf. DESCENT (theory of), NATURAL SELECTION, and ORTHOPLASY.

That organic evolution follows certain predetermined lines quite irrespective

of any 'selection' due to the action of the environment has been the belief

of many naturalists. Eimer terms such definitely directed evolution, to

which any selection which may occur is merely subsidiary, Orthogenesis.

'There is,' he says, 'no chance in the transmutation of forms. There is

unconditioned conformity to law only. Definite evolution, orthogenesis,

controls this transmutation. It can lead step by step from the simplest

and most inconspicuous beginning to ever more perfect creations, gradually

or by leaps; and the cause of this definite evolution is organic growth.'

Eimer has discussed his views in relation to the Lepidoptera at considerable

length. Many biologists fail to find in his discussion any indication of

the organic antecedents of particular lines of growth or transmutation.

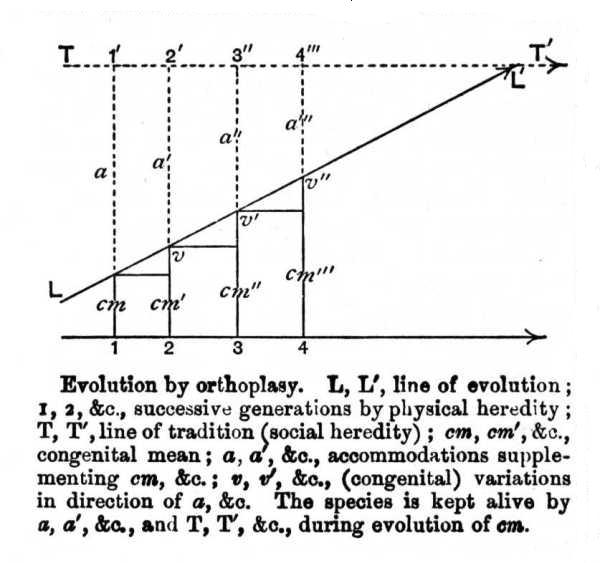

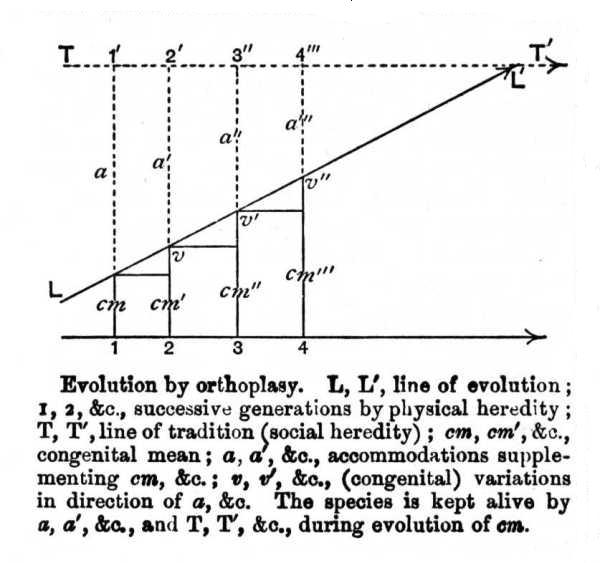

The conception would seem to be a form of vitalism, involving 'self-adaptation'